| |

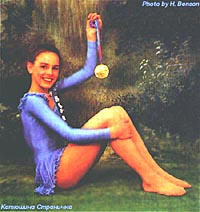

Americans fell in love with Katia Gordeeva at the Winter Olympics; she probably

did more for Soviet-American relations than any summit. The gold medalist in

pairs figure skating, Katya was a study in contrasts: a fragile-looking child

with the steely nerves of an experienced athlete.

Americans fell in love with Katia Gordeeva at the Winter Olympics; she probably

did more for Soviet-American relations than any summit. The gold medalist in

pairs figure skating, Katya was a study in contrasts: a fragile-looking child

with the steely nerves of an experienced athlete.Katia is what we like to imagine the New Russia - the Russia of glasnost and Gorbachev - will be: a strong force to contend with, but one that we can understand. Katia's quick fame was, in part, a reflection of American's deep faith in people-to-people connections, of our belief that if we know each other, problems of power and defense strategy will be more manageable. There is comfort in similarities. That is the very essence of the Olympics: to look beyond nationalism and find humanity in physical competition. It is not always easy. Many of the Soviet athletes are indomitable, frightening in their concentration on winning. However much we may admire them, they are difficult to embrace. Not so Katia. She was paired with her partner, Sergei Grinkov, when she was ten; and just a few years later, they appeared in their first World Championship and won. In the last twenty years, the Soviets have dominated pairs skating, passing world championships among themselves. The men are always stoic and strong, the women formidable athletes with impenetrable veneers. Katia changed that. In total medals collected in the Winter Olympics, the Russians finished first; the Americans, as one commentator put it, finished slightly ahead of the Fiji Islands. That is threatening - but Katia is not. When we hold her as the image of Soviet power, we can smile in satisfaction.

By Janice Kaplan |

Copyright © 1999 Irina S. All Rights Reserved.